Our history

Bristol Water has been proudly providing an essential public water service to the communities within and surrounding the city of Bristol since 1846.

Bristol Water – a social history

We've collated everything there is to know about our history and it's now yours to download and share.

The timeline

As with all the writings of historical recollection and reflection, this timeline is but one interpretation of the story that brought about the Bristol Water that operates today. There would have been a different history, had different archives been encountered or those archives been written and interpreted through a different lens.

How we see history is therefore a matter of perspective and so the timeline below will, to some extent, be a work in progress, reflecting the subtly changing perspectives and contributors to both historical records and current interpretations of our history. At Bristol Water we do not own our history but rather believe that our history is collectively owned by our customers, employees and community past, present and future.

If you have stories, articles or memories that can better articulate our understanding of this collective history that you would be happy to share, we would love to hear from you.

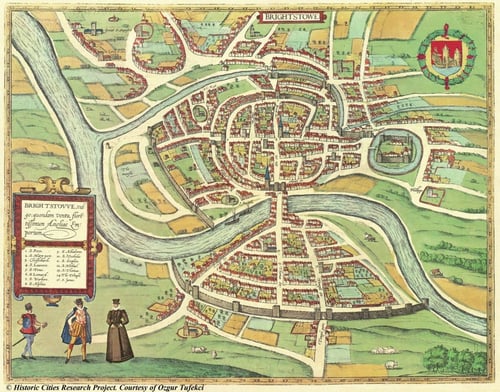

400 AD

Medieval Bristol

By the 15th century a number of conduits or wooden pipes were functioning, such as St John's Pipe from near Berkeley Square which still runs in Nelson Street; All Saints Pipe from Terrell Street, Kingsdown; Jacob Wells Pipes from Brandon Hill, supplying Bristol Cathedral and south of the city; Temple Pipe from Ravenswell, Totterdown; and Redcliffe Pipe from Ruge Well, Knowle.

Many of these medieval conduits were laid by religious communities to bring well water to serve their congregations, with some direct branches or "feathers" to supply important individuals or institutions. These conduits were often formed of elm, hence the coining of the word trunk mains ( reflecting these early materials used for the distribution of water).

For the remainder of the medieval period, the story of water supply in Bristol was localised and largely characterised by isolated groups of individuals serving their respective needs and interests. Development was in relative terms slow and the picture of a pest- and plague-infested port predominated.

1600 AD

The first Bristol Waterworks and the first organised supply of water.

5 February 1695

The founding of Bristol Waterworks Company. Population growth in Bristol was putting an increasing strain on the availability and accessibility of water sources to supply the city. Water pollution was rife and with the break-up of monastic institutions, many of the localised water systems fell into disrepair. Fear of the plague, and indeed fear of fire (following the great fire of London in 1666), meant those that could afford to pay for a private, direct and uncontaminated water supply would be willing to pay for the privilege. In response to this need, the idea of Bristol Waterworks Company was born.

1696

Not without opposition, the bill to create the first Bristol Waterworks Company was passed by the House of Commons, presented by the Bristolian Richard Bury and the Londoner Daniel Small, among others. Royal assent was granted to develop a water course, bringing water from the outermost reaches of the city's jurisdiction at Hanham Mills into the city via a reservoir at Barton Hill and a gravity- fed system of hollow-elm pipes thereafter down Lawrence Hill, Old Market Street and across Bristol Bridge.

1698

The Hanham Mills system was completed, although a series of financial and technical issues from the outset meant that supply was more often off than on.

1700 AD

Nonetheless, despite appearing thwarted from the outset, a situation often compounded by the less-than-cooperative Bristol Corporation, the first Bristol Waterworks Company lasted until 1782 – an 87-year history that is a seemingly understated chapter given that the company was portrayed as doomed to fail from the outset. Ultimately driven to debt and bankruptcy by the “undeniable sense of public duty” (Frederick, 1993), the waterworks passed into the hands of the Bristol Corporation and the works lay dormant for the next three decades.

Subsequently, more localised efforts across the city were made to seek a clean and reliable supply of water, although all were short-lived.

1800 AD

1811

An Act of Parliament was granted to a group of local men to construct a canal, bringing water from the Kennet and Avon rivers near Bath to serve the dual purpose of providing drinking water to the inhabitants of Bristol and provide a navigable passage for boats through to the Floating Harbour via Temple Meads, a scheme they had coined “The Bath and Bristol Canal and Bristol Water Works”. The intention was to utilise the redundant water courses developed by the Bristol Waterworks Company to serve all the Bristol parishes and surrounding areas via a series of pipes and reservoirs. The scheme, however, never made it off paper due to the high capital funds required.

1841

The Merchant Venturer’s Water Works was formed by businessmen who had identified a profitable market opportunity to supply the homes of Clifton village. The proposed undertaking resided on the wealthy Clifton clientele willing to pay for the service and the proximity to the Hotwell springs located beneath the cliffs upon which Clifton is perched, from which plentiful water could be drawn.

1842

The merchants put forward a parliamentary application to supply Clifton on this basis. However, it was subsequently withdrawn due to a member of the opposition, who benefited from a practical monopoly over the existing water supplies to Clifton, not taking kindly to the idea of a new rival. The withdrawal was only temporary, and with growing popularity among the residents of Clifton, the scheme was debated in parliament once more.

1845

A government commission was appointed to investigate the state of large towns in England. Their report for Bristol was a poor assessment insofar as it stated “there are large towns in England in which the supply of water is as inadequate as at Bristol”.

In the context of this report, the Merchant Venturers had at the time identified that their own proposed undertaking may be subject to political challenge given their intention “only to supply Clifton and the more wealthy parts of Bristol”, and that if asked to extend their undertakings to provide comprehensive supply to the entire city, the Hotwell springs would be inadequate.

1845/46

Rumour circulated of a rival philanthropic organisation which sought to supply the entire city of Bristol, residents rich and poor alike, by bringing in water from the Mendip Hills, several miles beyond the city boundary.

1845/46

A competition to win the right to supply Bristol with water was debated in the House of Commons, and with Brunel backing the Merchants’ cause, a recommendation was made by the Standing Committee that the Merchants supply the whole city. The verdict of the Parliamentary Committee was, however, to approve the rival scheme.

The birth of Bristol Water

16 July 1846

On 16 of July 1846 (a Thursday), the Bill of the Bristol Water Works Company (the II) received Royal Assent. Among the founders was a philanthropic core including Francis Fry, Quaker George Thomas and William Budd, a man of significant medical talent who was among the first exponents of the germ theory and the importance of sanitation. The Act of Parliament authorised the development of infrastructure to support the company’s supply of water from three main sources: the cold springs of Barrow Gurney, the spring at Harptree Coombe and the springs at Chewton Mendip, the latter of which was most important. The Line of Works, an 11m/18km viaduct, carried water from the Mendips to Barrow Gurney via a gravity-fed route of tunnels and culverts and onwards to the city. A reservoir was built at Barrow Gurney to receive the water, and also compensation reservoirs at Sherbourne and Chew Magna to maintain the flow of the River Chew. Service reservoirs were built at Bedminster Down, Clifton and Durdham Down to help maintain a constant flow of water to the city.

1 October 1847

By this date, water was flowing into the city via the Line of Works.

1854

The early days of Bristol Water Works Company can be considered a significant social and engineering achievement in both the realisation of the ambition to supply the entirety of Bristol with water and in the amazing feats of engineering that were accomplished in bringing water into the city from a significant distance away. Nonetheless, the company faced many challenges, not least landowning issues, open competition and customer complaints, but management went on undaunted, motivated to deliver a constant supply of clean water. Challenges were also commonplace in terms of water resources with a major leak at Barrow in 1854, which required draining the entire reservoir, followed shortly after by an extreme summer drought, the worst in 60 years.

1856

It was not until 1856 that the first dividends were paid and then only a modest amount. Subsequent years’ payments were similarly modest, if not disappointing with share values bought at £25 thought to only be worth between £8 and £9, demonstrating both the struggles faced by the infant company and the social views of the Board to reinvest rather than cream-off the margins.

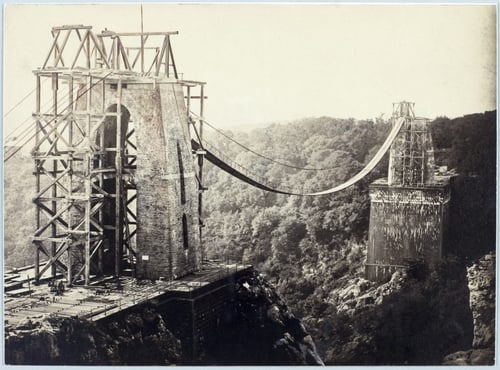

1862

A further Act of Parliament was granted to excavate a second reservoir at Barrow Gurney, with supporting plans to strengthen supply to Brislington and other nearby areas in Bristol.

1864

The drought of 1864 reached new precedents with records suggesting that some of the Mendip springs dried to a trickle. Emergency measures were taken to resurrect old wells and water systems, but this wasn’t sufficient to stop some places going without supply completely and others being restricted to two hours a day. All the while, the company had to meet increasing demand for water due to the growing population of Bristol in cause and consequence of the Industrial Revolution but also the growing industrial needs for Bristol as a port and factory city.

1865

In response to such external conditions, a further Act of Parliament was granted to develop a well at Chelvey to add to the incoming water received at Barrow Treatment Works. Around a similar time, financial prospects for the company looked up with the purchase of offices and premises previously leased at Small Street.

1871

Bristol Water Works Company celebrated its silver jubilee. Today, we supply water 24 hours a day rather than switching it off overnight in the summer, and supply around 20 times more premises than we did in 1871.

1877

Rising social expectations regarding health, sanitation and the ever-growing demand for water led to price increases and in turn healthier returns and dividends – in hindsight, perhaps a mark of thanks to those who persevered with the investment in the early days of Bristol Water Works. No doubt spurred on by the healthier margins and perhaps in regret of having not sought it earlier, the Bristol Civic Corporation sought to take over the company. The discussion was protracted and piecemeal and on the basis of unreasonable terms the matter was dropped, albeit only temporarily until it was reopened again by the corporation some five years later. The Board of Bristol Water Works successfully declined and fought off the respective challenge.

1882

A third reservoir at Barrow Gurney was built following the Act of 1882 which enabled further supply to be provided to suburban areas of Bristol, providing a total storage capacity of 870 million gallons at Barrow Gurney. Access to Sherbourne Springs further expanded the water resources available to support the growing demand.

1884

Monopoly rights to supply Bristol were less than secure with rival bills again seeking to impinge on the supply areas so far served by the Bristol Water Works Company and neighbouring regions. These were thrown out by the House of Lords in 1887.

1889

The Parliamentary Acts of 1888 and 1889 gave powers to construct what is known today as Blagdon Lake but is more accurately called the Yeo Reservoir. The damming of the valley was completed in 1901 with a network of local springs feeding into the reservoir in addition to the Yeo River. Around a similar time, filter sand beds were installed at Barrow, and this marks one of the many steps towards improving water quality. By this era, all of the original Board members had moved on or passed away. In their place were new individuals with new ideas but all still with the interests of greater societal benefit for Bristol in their mindset.

1900 AD

The great competition and the right to supply the city of Bristol with water…

1904

New offices and works yards were established to replace the now cramped work spaces on Small Street.

1914-1918

The First World War saw male staff departing for the front and with that the first female presence in the office of the Bristol Water Works Company. War inevitably hit the company hard, but the staff and Board could not fully let it preoccupy against business as usual and the pressing need to secure more water resources.

1920

Two years after the war, works began on sourcing water from the Cheddar Springs with associated pumping to take the water to Blagdon. The foresight of the Cheddar Scheme and subsequent construction of Cheddar Reservoir proved timely with the postwar expansion of houses on demand. The final part of the Cheddar works, connecting the reservoir to Barrow, was completed 10 years later.

1933

This year saw renewed attempts to investigate public appetite for the incorporation of Bristol Water Works into the civic corporation with the establishment of a committee under the corporation’s authority. The resulting report issued in 1934, no doubt to the disappointment of the corporation, concluded “that the steps taken by the company to safeguard the water supply would meet with general appreciation by the citizens, and that the situation did not provide occasion for pursuing further the question of purchase”.

1939

Once again, the staff of Bristol Water Works Company were all too soon fighting another war. The increasing mechanisation of the Second World War brought the war fronts closer to home. On one night alone, on 24 November 1940, in addition to the destruction on the streets and to homes, some 95 water mains were damaged. When enemy invasion seemed a reality, hundreds of rafts made of tree trunks were placed on the company’s reservoirs at Cheddar, Barrow and Blagdon to prevent the alighting of enemy aircraft. Throughout the war, all staff dutifully played their part to company and country, working all hours to restore supply often with little regard to personal safety. Despite best efforts, many parts of the city were without water supply. A survey was conducted by Bristol Water Works Company to locate the old medieval wells and conduits as an emergency measure, research which subsequently proved of significant historical value after the war.

1945 – The Water Act of 1945

This marked a major milestone in the development of the water sector. Prior to 1945, separate Acts of Parliament were required to permit the undertaking of any major works, but the Water Act changed the requirements governing water suppliers and extended and formalised duties to include conservation and appropriate management and use of sources

10 July 1946 – 1946

This was the centenary of the Bristol Water Works Company, and to mark the celebrations, the Lord Mayor of Bristol cut the first sod to commence the construction of Chew Valley Reservoir. The reservoir had been granted under the 1939 Act, but due to the war and the reallocation of company resources, construction had been postponed and permission to begin the scheme properly was only given in 1950. Postwar housing developments and reconstruction kept all staff busy in an effort to return to “normal”.

The era of expansion…

1950

The Public Utilities Street Works Act formalised working relations between local authorities and utilities. The company, again, sought new offices to reflect the war damage.

1953

The initial filling of Chew Reservoir began on 6 November 1953 with the scheme reaching completion in 1954.

1956

The Queen inaugurated Chew Valley Lake on 17 April, alongside the Duke of Edinburgh, in front of an audience of 1,000 guests – an event marking the first Royal opening of one of the company’s works. In response to petrol rationing as a result of the Suez Canal crisis, working hours of staff were changed to avoid unnecessary fuel wastage while queuing in heavy traffic – even back then, congestion was an issue!

1951/1960

The 1950s were characterised as an era of expansion as Bristol Water Works acquired in quick succession many of the neighbouring urban and rural district council water supply organisations and their respective supply areas. The largest acquisition was the combined takeover of West Gloucestershire Water Company on 1 July 1959, Shepton Mallet Waterworks Company on 1 January 1960, Glastonbury Corporation on 1 April 1960 and Wells Rural District Company on 1 October the same year, increasing both the supply area and population serviced by manifold.

1960

It was remembered as the year of the rain, with both Blagdon and Cheddar at capacity and overflowing by the end of January. While the summer was dry, the exceptionally heavy rain in October caused flooding in Somerset. The weather events of the year illustrated powerfully the lag effect of weather on reservoir levels and the seemingly ever-present need to develop new resources to meet growing demand. In response, Bristol Water in partnership with the British Transport Commission promoted a Bill in 1959/60 to abstract water from the Sharpness Canal outside of Bristol Water’s supply area to the north. Royal ascent was received in summer that year.

1961

This year saw further alterations to the setup of works and depots with relocations and consolidations across the supply area, no doubt in response to the recent amalgamations of other undertakers. Most notable was chosen to this end with the big move occurring in 1963/64. Perhaps one of the most major challenges in the move was relocating the company’s calculator, weighing in at over one tonne.

1961 - 1963

The winter of 1961-62 witnessed a prolonged cold spell over Christmas and into the new year when both Blagdon Reservoir and Chew Valley Lake froze over. The event, coined “Frostbite”, marked one of the biggest emergencies since the air raids of World War Two with burst and leak rates reaching record levels. 1962 held no respite with a frosty January and low rainfall throughout the year. 1963 concluded with a blizzard in December, known as the great freeze, in which the emergency responses of the company were again put to the test. 1963 also saw Royal Ascent of the Water Resource Act, which formally set out the requirement of water undertakers to protect, conserve and manage water resources.

1965

This year saw the introduction of Littleton Treatment Works bringing more water into supply from the Sharpness Canal.

1967

Saw the arrival of the new IBM 360 computer and the mammoth task of transferring records commenced. Sailing on Chew Valley Lake also started this year, although winter sailing was cut short due to an outbreak of foot and mouth disease.

1970s

Activities in the early 1970s might now be termed the Long Walk and involved surveying the proposed route from Purton to Pucklechurch and resolving the many associated problems – contractual, technical and otherwise – in order to bring more water into supply from Sharpness.

1971

Following many months and years of preparation, the company adjusted to decimalisation and metrication across the company’s equipment and records. Thoughts of reorganising the water industry to streamline the number of bodies responsible for water rumbled along, although no changes at the time were proposed to statutory water companies.

1973

The year saw a more formal proposal on reorganisation of the industry with the passing of the new Water Act in 1973 with the consolidation of local water undertakers, sewerage authorities and river authorities into 10 water authorities. To note, however, Bristol Water as a statutory water company was to have no major change to its functioning.

1974

When the water industry was restructured in 1973 into regional water authorities (the larger companies that were ultimately privatised in 1989), private water companies such as Bristol Water were allowed to continue to operate unchanged within this new national framework, because they performed well. When the Wessex Water Authority was founded its new Board and management included many people from Bristol Water, demonstrating the importance of a local connection that a privately financed company with a social focus already provided. Bristol Water also received a refund of its part in a new reservoir that helps support water supplies in the River Severn for many water customers, including in the area we serve to this day.

1976

This would be remembered as a year of drought across the country, the driest for 150-200 years. Increased reliance was put on the Sharpness Canal as a supply of water at this time, as underground water supplies were significantly reduced and evaporation from surface water stores peaked. The national response was the Draught Act, passed in July that year, enabling Bristol Water to ban the use of hosepipes and sprinkles in order to curb demand. 1976 also witnessed an effective attempt to nationalise Bristol Water among the other 27 statutory water companies in an extension of the 1973 Act to integrate them with the 10 water authorities. The Board undertook all necessary measures to ensure this eventuality was not realised. Later that year, a white paper was published, setting out that while not cancelled, the prospect of nationalisation did not have parliamentary support and was left to simmer.

1983

The year witnessed the first national strike in the water industry, and while it was short, it evidenced the importance of all staff to maintaining what is an essential service. The year also marked a milestone in the formal offering of meters to domestic customers from 1 April with the new “water box”. Bristol Water was the first to install the equipment at property boundaries.

1989

The nationalisation debate was concluded with the Water Act of 1989 receiving Royal Ascent. In effect, the Act meant the end of state-owned water authorities, and while Bristol Water was proudly never privatised, it removed for the foreseeable future the possibility of being brought into government control. Ten regional water and sewerage companies were privatised and Ofwat was created to monitor the sector.

2000 AD

Bristol Water today...

2001

Launch of a joint billing company with Wessex Water to issue and administer joint bills for water and wastewater to customers in the Bristol Water supply area.

2006

The delisting of Bristol Water from the stock exchange and purchase by Agbar.

2010

Bristol Water goes from Spanish ownership to English with the purchase of Agbar shares by Capstone, resulting in an ownership ratio of Capstone 50%, Agbar 30% and Itouchu 20%.

2014

Head office refurbishment including creation of an onsite catering facility and closure of Bedminster works depot.

2015

iCON purchase of Capstone.

2017

Retail market opening, meaning that non-household customers could choose between retailers for the billing of water services. Bristol Water exits the business retail market but continues to act as wholesaler. Water2business, jointly owned with Wessex Water, operates as our business billing (retailer) company.

2018

March 2018 witnessed the completion of the latest resilience scheme: the Southern Resilience Scheme. The scheme involved the laying of a pipe from Barrow to Cheddar to enable increased resilience for our customers in the Weston-Super-Mare, Cheddar, Burnham-on-Sea and Glastonbury areas and the northern part of Bristol. As a result of the scheme some 280,000 customers can now receive water from more than one treatment works meaning the probability of them experiencing supply failure is significantly reduced.

2019

Bristol Water launches its social contract, a framework for engaging with local communities to understand their evolving needs beyond water and to assess how and where we can add social and economic value through the services that we provide.